|

|

|

And so, I find myself travelling across America listening to these songs again, on a second-hand cassette, and wondering if I can make sense of everything this time. These are the songs that transported my teenage mind to another world, yet to be inhabited by anyone else. It’s a world that promised unconditional freedom and space to explore the nether regions of art. “We need new dreams tonight,” Bono might have sung, and it was never more appropriate in the world of this thirteen-year-old boy. Most people seek a record that allows them to define themselves, and The Joshua Tree by U2 is still the record by which I judge all others. Maybe because it entered my heart and mind at a time when I was looking for it and maybe because of that it has some sort of Holy Grail aura about it. I wore out four vinyl records, two cassettes, and two CD copies of this album trying to fathom how humans could possibly make music like this. These days it's pretty easy for me to deconstruct the album and see that it's a brilliant hybrid of rock, blues, country, folk, gospel, punk, ambient (Eno’s influence), experimental music, etc… But, way back when I couldn't figure out where this music came from, it didn't seem to fit into any particular place or time that I was aware of, and it still holds that mystery to me, somewhat. Most of the things that I'm interested in can be found within the grooves of this record. The ideas on The Joshua Tree are BIG, the themes it deals with are BIG, the landscape the music evokes is BIG. Everything about it, like America, is BIG. It sold over twenty million copies worldwide and put them on the cover of Time magazine. U2 made no bones about the fact that they wanted to be the Biggest Band In The World™ in 1987, because that seemed important in the era of stadium rock. This is music with ambition, the antithesis of indie elitism; in my own masochistic way it's the reason why I still hold it in such high regard. It’s easy to criticise U2 because their ambition often outweighs their musical ability, but also because ambition is typically frowned upon in rock ‘n’ roll and this is, of course, evident on The Joshua Tree. But there are very few definitive statements, or answers, to be found on this record despite the fact that U2 are often criticised for being overtly sincere. It is more a document of four young men, in their mid-to-late twenties, trying to discover themselves and make sense of the confusion in their lives through the boundaries of their music. And so, a journey begins...

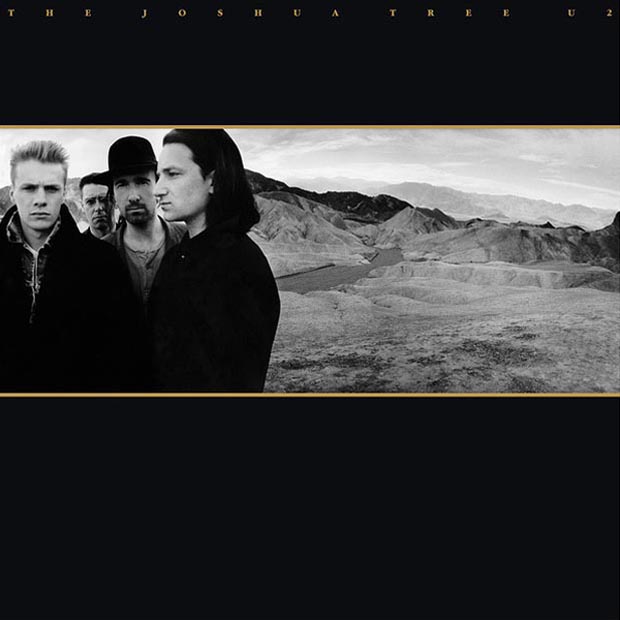

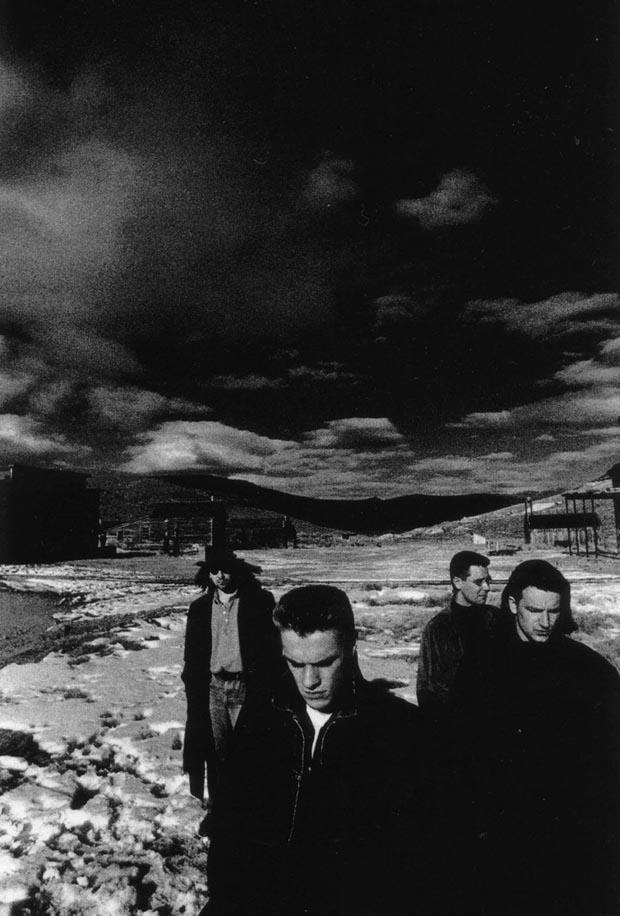

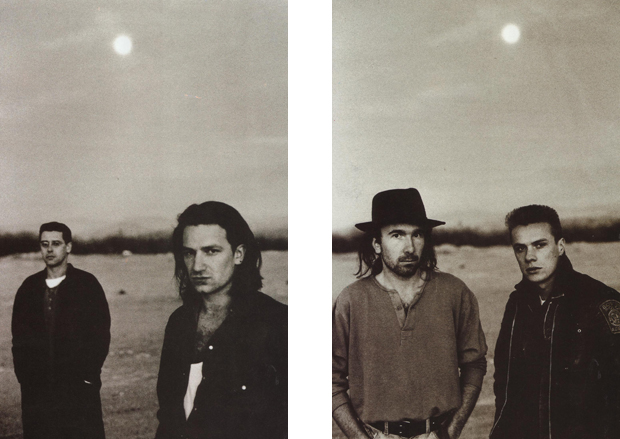

One of the biggest misconceptions about The Joshua Tree is that it is U2’s "American album". The truth is that only three of the songs deal specifically with the subject of America. There is no doubt that the initial inspiration for the record was the continent of North America, but that simplifies the issue here. U2 had already dabbled with the notion of America on their previous album The Unforgettable Fire, writing meditations on Southern icons Martin Luther King and Elvis Presley, even naming one peculiarly oblique song "Elvis Presley and America". However, the notion that The Joshua Tree is purely about America is one of the biggest red herrings in the story of the album. The album’s artwork probably has more to do with this impression than the music itself. It’s impossible to listen to this record without being influenced by the artwork it is packaged within because it is so powerful. Like all good album art, The Joshua Tree cover creates an inescapable mood for the listener before the record even reaches the turntable. The four figures on the front cover, set against the blank canvas of Death Valley desert, have the quality of Mount Rushmore sculptures carved into stone and hint at some sort of spiritual pilgrimage, or the Irish in America, perhaps. Steve Averill’s placement of the imagery within two black horizontal bands, instantly gives the viewer an introduction to the cinematic quality of the music and almost looks like a still from a Sergio Leone movie. Anton Corbijn’s striking photography sets the mood of the record and brings the songs themselves into a widescreen reality. In actuality, it was Corbijn himself who had suggested the idea of the Joshua tree as a visual motif. The early Mormon settlers in the Southwest States had christened the Joshua tree “the praying plant”, claiming its branches suggested the Old Testament prophet Joshua pointing the way to the Promised Land, so in many ways it is a perfectly appropriate title for the record. The dried-out basin of Zabriskie Point (clearly inspired by Antonioni’s movie of the same name) depicted on the sleeve reflects the death of spirituality in the 80s, the idealism of the 60s, and the spiritual life alluded to by America’s great poets, long forgotten, in the age of shoulder pads and hair-dos. U2 are nothing if not talented mythmakers and there is no doubt that U2 were aware of the overtones of Gram Parsons' death in Joshua Tree Park, California, in 1973. You only have to listen to the Joshua Tree’s follow-up record, Rattle And Hum, to discover how buying into the mythology of rock ‘n’ roll can cause a band to fall completely flat on its face.

Considering the fact that U2 were the biggest band in the world in 1987, the sound of The Joshua Tree is perplexing in many ways. It is completely left-of-field of synth-pop and the majority of other things that were happening in music at the time. Music had become awfully clinical in the 80s, with the majority of artists favouring machines instead of humans to make music. Mistakes (that is, humanness) had virtually been eradicated from the recording process and the advent of compact discs, two years earlier, had led the recording industry in a search for more 'clean'-sounding recordings. Recorded, for the most part, in the drummer's spare bedroom, the sound of The Joshua Tree is similar to the feeling of gospel recordings in terms of capturing the spirit of a room and embellishing the soul, and flaws, of the performance. The band’s choice to stay away from regular recording studios and find rooms that suited the environmental nature of the songs is pretty radical when put into this timeframe. U2 had often raised the issue with Brian Eno of producing music that would give the listener the sense of a physical location. Each song on The Joshua Tree has an individual sound and there is very little common ground, sonically. This approach has a great deal to do with the album’s appeal, but it also has an almost extemporaneous quality akin to The Beatles’ White Album. The band had quite clearly immersed themselves in American literature prior to recording. Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and the short stories of Raymond Carver were to prove major inspirations on the subject matter of the album. The influence of these writings is clear on the track "Exit", but also on the overall atmosphere of the record. Eno’s influence on the recording is plain to hear, particularly on album’s final three songs, which form what The Edge called a ‘death suite’. There is an eeriness and tension in the recording that can only materialise from a group of musicians playing live in the same room together. The songs are claustrophobic and suffocating, and yet there is an element of space in the recording that, without question, conjures up images of an American landscape. The flaws in the album’s recording and production are definitely part of its attraction and produce an almost camera obscura-like effect. Every U2 album had been some sort of concept album: Boy deals with the loss of childhood innocence, October with spirituality; War is kind of self- explanatory and The Unforgettable Fire is knowingly esoteric. The Joshua Tree is a “concept” album in the same way that Sgt. Pepper is a “concept” album: it’s a collection of songs based around an original starting point that got shifted somewhere along the line and ended up becoming something completely different. This is no bad thing; the record is far more varied because of this standard artistic process. The layered and atmospheric keyboard introduction to "Where The Streets Have No Name", combined with the album’s artwork, immediately conjure up images of the vastness of southwest America. Let’s not kid ourselves that the striking imagery of the album’s cover does not have an influence here, especially when you consider that the roots of this song are firmly planted on a Belfast street where it was possible to tell how much money people earned and what religion they were just by which side of the road they lived on. It is a song of transcendence, of elevation, and is the sound of how potent a band could be in 1987. Today Bono maintains that the lyrics are incomplete, although at the time of their writing he was supposedly in accordanace with Eno’s claim that they were already finished--a claim backed up by the remarkable story of an impatient Brian Eno attempting to sabotage the track and erase the master tapes in order to get the album moving. It’s trivial to speculate that any great song can have just one specific theme as its focal point. Bono has admitted the influence of Wim Wenders’ 1984 film Paris, Texas on "Where The Streets Have No Name". Wenders’ story of one man’s journey to the desert in order to escape an urban situation is used as a metaphor for the country that Wenders says has “colonised our imaginations.” What is interesting about Paris, Texas and "Where The Streets Have No Name" is that they are both inspired by America's "mythic dream" as seen from a European viewpoint. The song in many ways reflects Irish ambiguity towards America. It takes us on an ethical and emotional journey through the suburban streets of Belfast, or, perhaps it’s the road from the Nevada desert into Las Vegas and back again, where the streets do, literally, have no name. For Europeans, what "America" oozes is both exciting and perplexing: the immense scale and beauty of the wide-open landscape set against the cheap strip malls that populate virtually every American town; the American dream as opposed to the reality of modern-day America. It is a country of many contrasts and confusions. For all its perceived po-faced arrogance, The Joshua Tree is an uncertain record, one that promotes doubt as much as it does faith. "I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For" is fundamentally a spiritual quest that offers no definitive statements or answers. It is an example of Bono’s experiment to write lyrics for the first time rather than write “at the mic” which had been his typical practice on previous U2 albums. On the surface it sounds like an attempt to write a gospel song but is in actuality rooted in the new wave movement of the late seventies rather than the primitive yearnings of the 1920s. Bono’s claim that the band tried to bring an old gospel tune into the modern day is basically a double-bluff. Listen to "Desert Of Our Love" (the song which gave rise to I Still Haven’t Found…) on the remastered and expanded version of the album to discover that the rhythm and melody borrow heavily from Patti Smith’s “Redondo Beach”. This early version of the song sheds new light on its conception and it is fascinating to discover it was born out of improvisation, as is much of the album. U2, along with Daniel Lanois, basically added some sort of authenticity during the production stage. The first twenty seconds of "Running To Stand Still" are a great example of how to create an atmosphere of American authenticity. The tagged-on slide guitar part, played by Lanois, gives the listener a feeling of the American West despite the fact that the song is about drug trafficking in Dublin. This is not a criticism in any way, but it’s a great insight into a mood that permeates the whole record. Despite its gospel leanings, "I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For" does not allude to America in any sense although it lyrically borrows from the gospel tradition of biblical symbolism and is lyrically reminiscent of the Psalms of David. Perhaps the centrepiece of the album, "With Or Without You" is a song of longing and Wanderlust. Despite its bizarre arrangement, incorporating Eno’s trademark arpeggios and the haunting, sustained sound of the Infinite Guitar, it provided U2 with their first American number-one single. The mood influenced by Scott Walker’s 1984 album Climate Of Hunter, it is a brooding masterpiece that transcends borders, nationalities, and boundaries like all great music should. Its a song about being faithful to your art and your lover at the same time and Bono insists that it is a song about “how I feel in U2 at times: exposed.” "With Or Without You" stands out from the rest of the tracks on the record as it is clearly not an ensemble piece. There is a distinct lack of acoustic instruments until the final half of the song, which is one of the reasons it is difficult to reproduce in a live situation. Larry Mullen’s drumming really is a tour-de-force, but great credit must go to Daniel Lanois’ layering of the various drum tracks during the song's finale. I have a theory about Bono’s lyric writing and it is that he typically writes about the weather. Check it! This is commonplace on The Joshua Tree where the elements are mentioned in virtually every single song. It works, and gives most of the songs an almost biblical quality. On paper the lyrics for The Joshua Tree read like U2's very own Book Of Revelation. There is a river that runs through The Joshua Tree. It's a river that runs through the wastelands of America until it runs dry in the the desert. The abstraction of the lyrics actually helps the listener to project their own imagery onto the songs. The Joshua Tree was born, slap-bang, in the middle of the 80s, hot on the heels of their acclaimed Live Aid performance. The band had interrupted sessions for the album to serve as the headline act on Amnesty International’s A Conspiracy Of Hope tour in 1986. The shadow of Reagan’s America hangs over this time frame. "Bullet The Blue Sky" is a song inspired by Bono’s own experiences on a trip to San Salvador and Nicaragua, where he witnessed the distress of peasants being bullied in internal conflicts. The song juxtaposes antipathy and anger towards the United States foreign policy in Central America. Bono, at the time, said he “had to 'deal with' the United States and the way it was affecting me, because the United States is having such an effect on the world at the moment. On this record I had to deal with it on a political level for the first time, if in a subtle way." Bono’s order to The Edge to “Put El Salvador through your amplifier” is kind of absurd, but it is a remark born out of hopelessness and anger. The track is bombastic and totally at odds with the notion of America as "the land of the free". It serves, rather, to contrast that concept with the Amerika that supports war in other countries. The time U2 spent touring the States in the early 1980s (viewing the American landscape from the windows of their tour bus, stopping over in gas stations and motels, hours spent listening to NPR and discovering artists such as Willie Dixon and Archie Edwards) obviously influenced their musical direction. . The influence of the blues can be heard on the guitar playing on "Bullet The Blue Sky", the only song on the whole album to feature the rock convention of a guitar solo. Along with "Bullet The Blue Sky" and "Mothers Of The Disappeared", "In God’s Country" is the other song on The Joshua Tree that specifically deals with the subject of America. There is almost a narcotic quality to the lyric that bemoans the spiritual death of a nation. “Sleep comes like a drug” and “we’ll punch a hole right through the night” are lines that could have been lifted from the pages of a Raymond Carver novel. The Statue of Liberty’s dress torn in ribbons and bows hints at the state of America in the mid-Eighties. One of the reasons that U2 were, and still are, unfavoured by rock critics is their tendency to make sweeping statements. What gives an Irish band the right to comment on the state of modern day America, or a supposed Christian band the right to comment on drug abuse (a major source of 80s lyric writing) in Ireland? Well, good art should always reflect the health of the society and great art should always over-stretch itself. Rock music can be ambitious and still be personal and that is what makes this album so great. The most revealing moments on The Joshua Tree are found in the hidden depths of songs like "Running To Stand Still". Again, born out of improvisation, this melancholic view of an Irish couple putting everything on the line to traffic drugs in order to escape Dublin is often misrepresented as a song about a heroin addict. In many ways the song is out of step with the rest of the record, but the building bolero rhythm and blues harmonica help it to fit with the ache, and the bluesy quality of the album."Red Hill Mining Town" is another song that turns its attention to Europe, offering thoughts on the British miner’s strike. It was actually slated to be one of the singles from the album, but was eventually pulled, possibly due to the appalling video the band made to support it. It's interesting to note that the songs that were written before the sessions were "With Or Without You", "Red Hill Mining Town", "Womanfish" and "Trip Through Your Wires". The latter two are almost throw-away in their bar room blues nature and luckily "Womanfish" didn't make the final cut. Another song that didn't make the album is "Silver And Gold", written by Bono (a first attempt at writing a blues song). An earlier version of the song appeared on the album Sun City, a collection of songs by Artists Against Apartheid. This version of the song features Keith Richards and Ronnie Wood of The Rolling Stones, who had introduced Bono to the blues. There is a naïvety, and ignorance of rock 'n' roll, in this record and it is one of the things that makes The Joshua Tree so enchanting. The sequencing is key to how we perceive the album today. The Edge told Hot Press magazine in 1987 that "We disagreed vehemently about what songs should go on the album. If Bono had his way, The Joshua Tree would have been more American and bluesy, and I was trying to pull it back." In the end, "Silver And Gold" was issued as a b-side. Its exclusion is intriguing, as many of The Joshua Tree's hidden secrets can be found in this track. A song about oppression, it probably would've been too obvious in the greater scheme of things. It is, however, one of U2's most vital works and would have fit into the “death suite” that closes the album. This trilogy of songs consists of "One Tree Hill", about Greg Carroll, the U2 roadie who died in an accident on Bono's motorcycle in 1986; "Exit", a song inspired by the epic mood of Norman Mailer's The Executioner’s Song, and "Mothers Of The Disappeared", written about the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, the mothers of the thousands of "disappeared” people who opposed the Videla and Galtieri coup d’état that overtook Argentina in 1976. "Exit" caused major controversy shortly after the The Joshua Tree's release when it was cited in the trial of the subsequently convicted murderer John Robert Bardo. In his defence he claimed his actions were inspired by the lyrics of the song. The story drew obvious comparisons with Charles Manson, who claimed that he was inspired by The Beatles song "Helter Skelter”. Bardo unsuccessfully blamed the song, an admittedly dark and intense piece, for driving him to commit the murder of the television actress Rebecca Schaeffer. Bono's reaction to this was to suggest that it sounded like a clever lawyer trying to create a novel defence.

The Joshua Tree's legacy is one that U2 have tried to play down on many occassions since the album's release. Its commercial success and earnestness were clearly a burden and they famously said that 1991's Achtung Baby was "the sound of four men chopping down The Joshua Tree." Achtung Baby is probably the group's best album, but The Joshua Tree is the sound of a band reaching it's peak for the first time, which is always compelling. The story of The Joshua Tree is really one of a journey. It’s a journey between the desert and civilisation. It’s a journey on a quest to discover oneself through the detours of art. It’s a spiritual road movie through the heartland of America. For me, the record has taken on a life of it's own and is about my journey from adolescence to adulthood. It signifies that overpowering moment when someone's eyes open to the possibilites of the world for the first time, and it has that quality every time I listen to it. This album has always been a major distraction for me because it constantly serves in my mind as some sort of barometer of personal progress, or lack thereof, and I will often find myself questioning how much my life has really changed since it was released in March of 1987. U2 strived for what could be called the 'indescribable in art' with this record. They may not have made it at times, but there are very few things as engaging as watching, or hearing, someone strive for greatness even if they fail. Ultimately, there is a sense of hope and some sort of ecstatic longing on The Joshua Tree which is probably why I reach for it over and over again.

|

|