|

|

|

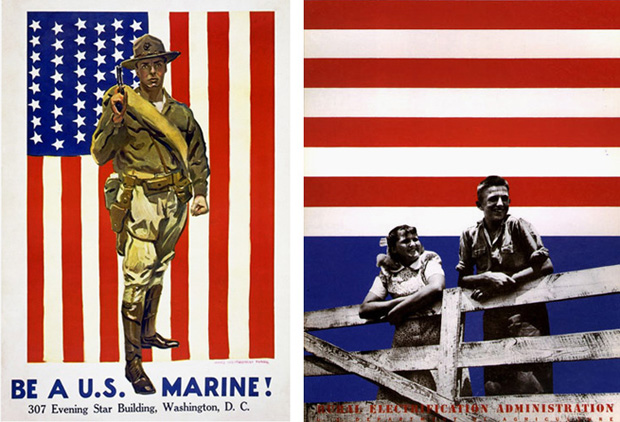

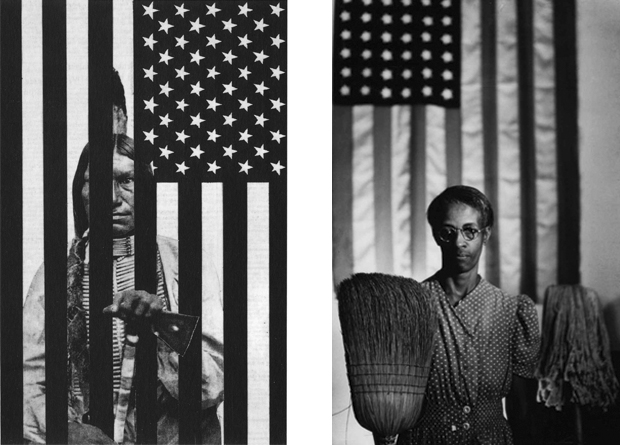

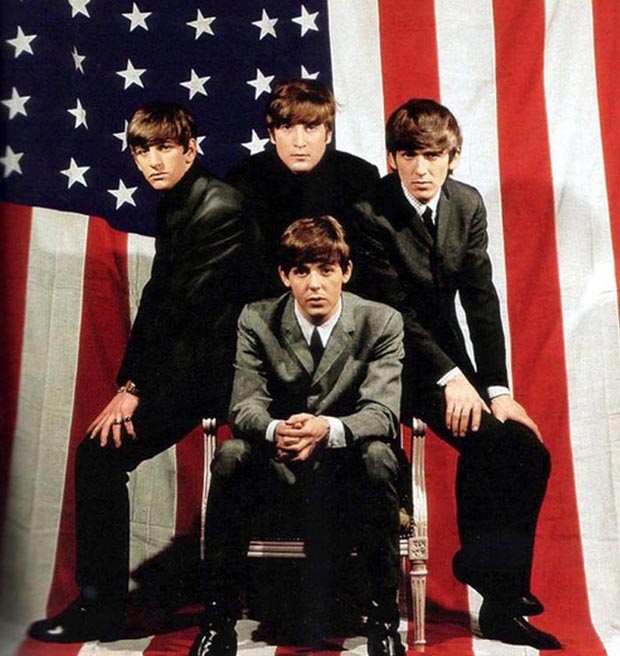

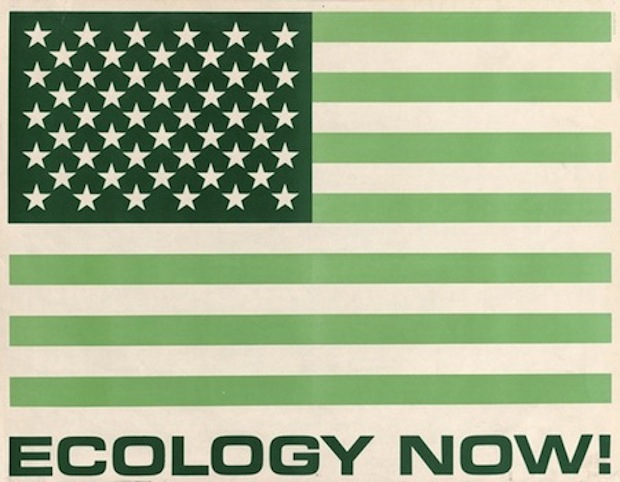

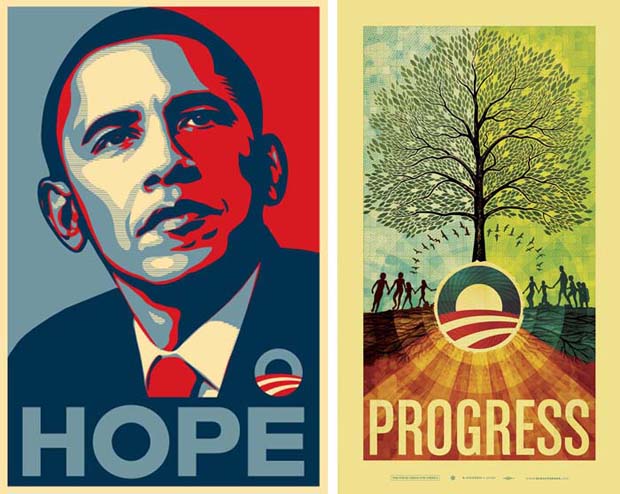

The American flag, despite all of its aesthetic changes over the years, remains a potent symbol of American democracy and independence. The Stars and Stripes supposedly represents all that is good about America, yet its use in popular culture has seen an inversion of its symbolism. The 20th Century saw infinite uses of the American flag in the fine arts, propaganda, advertising, and photography, and as a pertinent symbol of protest. Government-endorsed recruitment posters are the first example of the flag's use in print, posters that one hundred years later would be viewed as a display of disregard for flag etiquette. The dramatic social changes of the 1960s and the ensuing War in Vietnam provoked an unparalleled re-writing of the American flag's ideology. The period from Jasper Johns' flag canvases through to the angry protests against America's involvement in Vietnam saw a shift in the public's view of America's most sacred symbol. There is no history book concerning the graphic language of the American flag and this essay aims to bring together relevant examples of its use in order to clarify its influence and importance. This essay attempts to find out artists' motivation in using the American flag as a graphic icon and to understand the current relevance of the Stars and Stripes. Examples of the flag's use in modern culture are inexhaustible. I've attempted not to include any examples that have not instigated any specific change or argument. America's Declaration of Independence from Britain on the 4th July, 1776, resulted in the birth of a new national flag in 1777. The first Flag Act, passed by the Continental Congress, resolved that the flag of the United States be made of thirteen alternate red and white stripes and thirteen white stars on a blue field, in order to represent America's thirteen states and the country's democratic Government. The colours red, white, and blue, though clearly derived from British sources, are open to interpretation. George Washington declared: "We take the stars from heaven, the red from our mother country, separating it by white stripes, thus showing that we have separated from her, and the white stripes shall go down to posterity representing liberty." A book published in 1777 by the House of Representatives stated that "the star is a symbol of the heavens and the divine goal to which man has aspired from time immemorial; the stripe is symbolic of the rays of light emanating from the sun." Although the first Flag Act specifies no particular symbolism to the flag, white is a colour believed to signify purity and innocence; red, hardiness and valour; and blue, vigilance, perseverance, and justice. The first stirring of the flag's power was documented at the battle of Fort McHenry in 1814. In a poem that would later become the American national anthem, about the banner that survived British bombardment, the poet Francis Scott Key wrote: "...broad stripes and bright stars, thro' the perilous fight... Oh, say, does that Star-Spangled Banner yet wave... and the Star-Spangled Banner in triumph shall wave." No modern icon is more resistant to aesthetic transformation than the American national flag. The flag is instantly recognisable to the uninitiated viewer because of the simplicity of its grid-like structure. The emblematic nature of its design is also very different to any other nation's national flag. The flag's structure is striking in its originality, and is left open to graphic interpretation because of this. The Stars and Stripes can be seen as a negative or positive symbol by the viewer just because of its placement. It is this flexibility that has prompted its widespread use in popular culture. The American national flag thrives on its customary omnipresence. No event procession or concert is complete without it. Seen as a symbol of national unity and of a prosperous state, it is impossible to find another nation that pledges such allegiance to its national emblem. American school children are brought up to sing the Star-Spangled Banner, with hand on heart, every morning during school assembly. The increasing use of the American national flag as a patriotic symbol enables us to draw comparisons between the Stars and Stripes and the Nazi Swastika. "No country has a more elaborate cult of its flag than America, or a more general reverence for the flag as a kind of Eucharistic symbol." Presidential Inaugurations are a prime example of an overuse of the flag as an icon of the American Dream, which reeks of distasteful propaganda. The sheer scale and magnitude of the Stars and Stripes projected onto television screens around the world makes for uneasy comparisons between Presidential Inaugurations and Leni Riefenstahl's cinematic documentary of the 1934 Nazi Nuremberg Rally, Triumph of the Will. If the American public continues to protect and display its national flag in this way, it could lead America to be viewed in the same way that South Africa was during Apartheid, or like Nazi Germany. The poster as a political instrument reached maturity during and after World War 1 and again established its influence during the Russian Revolution. Because of America's detachment from Europe, many Americans then regarded propaganda as alien and un-American. Despite this, the American government printed and distributed more than twenty million copies of over 2,500 political posters during the war; the most iconic of these designs were often provided by the illustrator James Montgomery Flagg. The Americans rallied with a populist approach, using everyday images derived from well-known magazines and book illustrations of the day. Recruitment appeals were made through realistic characters and ordinary people. James Montgomery Flagg borrowed the finger pointing concept of his I Want You For U.S. Army poster from the graphic legacy of three other nations, specifically Alfred Leete's British counterpoint, Your Country Needs You from 1914. Despite this, Flagg's reinvention often tends to overshadow the originals, proving that a great poster can often become the very symbol of a particular cause or historical event. "It is sobering to realise that even the most original piece of American iconography is rooted in precedent." Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels understood the power of aesthetics and utilized it during the Second World War. What the United States learned during World War 2 was that the iconic nature of the nation's flag could lead men into battle. Flagg's Uncle Sam and Marine posters are a perfect example of the power of the Stars and Stripes as a persuasive graphic symbol. Flagg's 1944 poster We'll Finish The Job carries the slogan "Jap... You're Next!", and displays an image of Uncle Sam, clothed in the Stars and Stripes, rolling up his sleeves in anticipation of confrontation. This poster typifies the use of the 'gung-ho' type of patriotism often found in American propaganda posters of the period. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 triggered an economic crisis and plunged America into the Great Depression. During these painful years, Federal programmes attempted to revitalise the country through a number of original poster campaigns. The national flag appears in many posters of the era. Such a compulsive symbol, the flag was used to magnificent effect by the graphic designer Lester Beall. His series of posters designed for the American Rural Electrification Administration are a beautiful interpretation of European modernism. Despite the adversity of the times, Beall managed to use the flag in a positive and patriotic light to produce a lasting affirmation of American spirit and resolve. In 1945, photographer Joe Rosenthal captured what many consider the definitive images of the American military in Iwo Jima, Japan, images that would inspire a generation in the same way that James Montgomery Flagg's posters had done some thirty years earlier. Rosenthal took a series of photographs as American soldiers won the battle of Mt. Suribachi. Earlier that day, he had noticed how iconic these images of the American flag-raisers could be as he watched the Marines mounting the victory flag. Rosenthal asked the soldiers to recreate the scene and promptly produced an image that symbolises American patriotism and valour. The American public, brought up on World War 2 movies and John Wayne Westerns, recognised and appreciated the patriotic sentiment of the image. The dramatic fashion in which the flag is symbolised is, to many, a vindication of its stature as a representation of American freedom, a freedom that has been fought, and often died, for throughout the country's history. America's costly defeat in Vietnam led the American public to view the national flag in contrasting ways. No statue, monument, document, or artefact says "America" so eloquently as the red, white, and blue of Old Glory. Seen as a symbol of one nation under God and shared values, the flag led men into battle and was sanctified by the blood of the patriots. The flag is such a significant emblem in the United States that many soldiers say that they fought for the freedoms and principles that made America great. The flag represents those freedoms. "Freedom is what makes the United States of America strong and great - it is what has kept our democracy strong for more than two hundred years," says Gary May, who serves as the chairman of Veterans Defending the Bill of Rights. "The honour veterans like me feel is not in the flag itself, but in the principles the flag stands for and the people who have defended them." This statement is in stark contrast to the American public's new-found distrust of the national flag. The American poster boom of the sixties led to a new wave of socio-political commentary by many of the era's artists and designers. The rise of underground culture and the free press eventually helped to force the withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam in 1973. Although the poster and underground magazines may be ephemeral, the overriding effects are not. "Press images and posters can become icons of an era, marking turning points in past history." Seymour Chwast's 1967 poster, End Bad Breath, is a classic example of anti-War graphic design. As with many of the era's posters, Chwast uses an eclectic mix of propaganda and illustrative motifs that revive earlier art movements, such as Art Nouveau. Send Our Boys Home by Christos Gianakos uses the American flag in a more literal sense. By changing the blue canton (where the white stars usually appear) into a black void, Gianakos manages to completely offset any affection that the viewer might have for the national emblem. The caption "Send Our Boys Home", which appears at the bottom of the flag, is a visually understated plea for harmony. Both Gianakos and Chwast successfully combine irony with the iconic and patriotic symbolism of the Stars and Stripes in order to poke fun at America's past and to encourage the American public to contemplate new sensibilities. The advent of the Cold War in the 1950s saw America rise to its highest levels of world and consumer power. The materialistic emphasis of mass production also instigated a wave of discontent within America. The economic boom led to uneasiness and new divisions between many facets of the American public. Dividing lines were drawn between the "haves" and "have-nots" and racial tension once again came to the fore. The dawn of the Civil Rights movement in America during the 1960s saw a reaction to the ideals of justice and equality as outlined in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, symbolised by the American flag. By the time of the rise of the Black Power movement, the American flag had begun to be seen as a symbol of oppression and exploitation of African-Americans. The Black Arts Movement, also known as the Second Black Renaissance, took place roughly between 1965-1976, suggesting a comparison to the Harlem Renaissance of the twenties and thirties. Both movements emphasised racial pride and commitment to produce works that reflected black culture and experiences of black people. Photographer Gordon Parks captured the bigotry and discrimination that existed in this period in the photograph American Gothic. The image, which mimics Grant Wood's 1930 painting of the same name, is considered to be Parks' signature image. American Gothic was taken in Washington, DC, during the photographer's fellowship with the Farm Security Administration, a Government agency set up by President Roosevelt to aid farmers in despair. Parks was outraged by the blatant racism that he encountered on his first visit to the nation's capital, such as being made to enter restaurants through back doors and being refused admission into movie theatres. Ella Watson was a black charwoman who mopped floors in the FSA building. Parks asked her about her life and photographed her in front of an American flag in the FSA offices. The image stands as an embodiment of African-American pride and as an indictment of American values. Its publication on the front page of the Washington Post in the 1960s helped to turn the image into a symbol of the pre-Civil Rights era's treatment of minorities. The Civil Rights freedom marches on Alabama led by Martin Luther King were a further indictment of the American Declaration of Independence. Demonstrators carried the Stars and Stripes in defiance and as a symbol of America's forgotten promises to, and violence against, African-Americans. In the sixties and seventies black artists used the flag in their work to highlight the contradictions between the official narrative of the Declaration of Independence, which proclaims justice and equality for all as the law of the land, and the everyday realities of discrimination against African-Americans in the socio-economic and human rights spheres. For example, the Confederate Southern Cross is offensive to many African-Americans because of the pro-slavery stance taken by the Confederate states during the American Civil War of the 1860s. The rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 60s and 70s contributed to the creation of racist stereotyping of African-Americans. Artists such as Faith Ringold, Jeff Donaldson, and David Hammons confronted these stereotypes head-on and represented a generation of artists who used the American flag as a symbol of institutional racism. Jeff Donaldson began work on his most renowned painting, Aunt Jemima and the Pillsbury Doughboy, on 28th August 1963, the day of the famous Civil Rights march on Washington, DC. Donaldson believed the protest march to be futile and was convinced that the next struggle would have to be confrontational if African-Americans were to finally secure their rights. The painting portrays this confrontation, simultaneously identifying the enemy and asserting Black-America's strength to overcome racial oppression. The subversive nature of this painting extends to the American flag. The stripes of the flag are bent into angular shapes, reminiscent of the Nazi Swastika, challenging the notion of democracy and freedom associated with the flag. Donaldson's painting also manages to draw connections between American racism and the recognised atrocities of Nazism. It is not only in the fine arts that African-Americans have tackled the subject of racism and oppression. Many graphic designers and illustrators also used their skills to make social comment during the sixties and seventies. In 1969 Gary Viskupic produced a poster for the Martin Duberman documentary film In White America. The stark black and white image graphically exhibits an African-American with his head in a noose and shrouded by a Stars and Stripes banner. Viskupic makes use of the new-found graphic language of the era to produce an image that is both unsettling and thought provoking. The use of the American national flag in the image makes a powerful statement about oppression and attitudes towards blacks in white America. Faith Ringold practiced in fine art during the sixties. Seen as an important political commentator, her work has led her to be regarded as one of the leading female African-American artists of the era. Ringold's definitive statement is a poster for the People's Flag Show held in 1970, a denouncement of Americans who still continued to show pride in their national flag. The poster makes a bold statement: "The American people are the only people who can interpret the American flag. A flag which does not belong to the people to do with as they see fit. Should be burned and forgotten. Artists, workers, students, women, third world peoples, you are oppressed. What does the flag mean to you? Join the people's answer to the repressive US Government and state laws restricting the use and the display of the flag." The announcement is treated like a hypnotic icon, inviting the viewer to extract information from it. The message of the poster is further enforced by the layout, which simulates the American flag. Her use of purely red and black signifies the oppression that many African-Americans feel and is reminiscent of the African-American Flag which was used as an emblem by the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Marcus Garvey proposed the flag for the association, which he founded in 1917. The African-American Flag uses a tri-colour of red, black, and green and first appeared in 1920. Garvey understood that Africans at home and abroad needed their own flag, as other flags around the world did not represent the collective of African people. The flag has become a symbol of the African-American experience. The use of red, black, and green represents the official colours of the African race. "Red symbolises the 'colour of blood which men must shed for redemption and liberty,' black, 'the colour of the noble and distinguished race to which we belong' and green for 'the luxuriant vegetation of our Motherland.'" David Hammons resurrected the African-American Flag for an exhibition at the Institute for Contemporary Art in New York at the outbreak of the Gulf War. Hammons used the colours of Marcus Garvey's African American Flag for his own interpretation of the Stars and Stripes. Hammons said "I made my flag because I felt that they needed one like the US Flag but with black stars instead of white ones." Intended as a positive statement about being an African-American, the flag caused controversy as people condemned it as unpatriotic and the institute received threats of violence as a result. The bloody atrocities of the Vietnam War led to a widespread public disregard for the American national emblem and its various connotations. For the first time, mainstream designers began using the flag in a derogatory way in order to make social comment. In 1970 Starfish Productions produced a poster that for many defined the injustice and partiality of a nation which continued to pledge allegiance to its national flag. The poster features an image of the Civil Rights activist Dick Gregory, with the Stars and Stripes painted onto the right-hand side of his face. The slogan reads: "I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the republic for which it stands, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all." Such a damning condemnation of America's First Amendment and its national symbol is a poignant reflection of Martin Luther King and his militant, non-violent principles. At the dawn of the sixties a new generation of artists set out to counter the high aspirations of the American Abstract Expressionists who preceded them by using the everyday and mundane, which had become modern-day life itself. The Abstract Expressionist stance of negation and alienation could not hold out and didn't. New American art would have to comment on the changing landscape of America. If Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning represented the 1950s and Abstract Expressionism, then Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns have to be seen as the figureheads of contemporary art in the 1960s. Rauschenberg and Johns spearheaded a new movement and the shift from Abstract Expressionism to Pop art was instigated by the pair. Together they boldly incorporated popular imagery in their paintings, with varying degrees of wit and irony. By 1955 Rauschenberg and Johns were seen as the most important working artists in New York City. The first appearance of Jasper Johns' flag paintings was ironically as a small panel in Rauschenberg's assembledge piece Short Circuit in 1955. A hybrid work, Short Circuit is a defiance of the values that dominated the New York art world. Impressed by the emblematic quality of John's work, Rauschenberg encouraged Johns to explore the new radical direction of his work. Because the mid-50s represented a peak in the American public's view of the Stars and Stripes as a symbol of nativist conformity, Johns was dealing directly with the nation's most charged public symbol. Flag, painted in 1955, presented the national symbol as a completely neutral emblem and single-handedly drained the dramatics out of both the flag and Abstract Expressionist technique. It played on the notion of "Is it a flag or is it a painting?" Many questions arise from Jasper Johns' Flag painting and Johns himself is reticent in explaining his motives. During the period of Johns' first exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, in 1952 and the first showing of his flag paintings in 1958, Johns had managed to subvert prevalent conceptions of reality and perception. His stance opened up new channels through which contemporary artists were able to discover expression through objectivist realism, and it opened the door for the new art of the sixties. Johns and Rauschenberg were joined by such artists as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine, and Claes Oldenberg, all of whom incorporated imagery skimmed from popular culture in work that they presented as fine art. The onset of the new values instilled by Rauschenberg and Johns was seized upon by new American artists. Countless contemporary artists explored the subject matter of cultural icons during the 50s and 60s. Swiss-born photographer Robert Frank travelled to New York in 1955 to begin a career in commercial photography. He set out on a tour of the United States, following no apparent plan except to produce a photographic record of his travels. The ensuing book The Americans was published in 1959, with a foreword by Jack Kerouac, and offers a nihilistic view of modern American life. Frank's photograph Fourth of July-Jay was one of many that captured the American flag, often being used in a derogatory way. The image reveals how a certain kind of American identity is passed on from generation to generation. The American flag's ubiquitous presence during the sixties transposed into other creative fields outside of the fine arts. In 1969, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper produced the most iconic film of the decade in Easy Rider, a film that encourages its audience to question the values of the national flag. Dennis Hopper was actively involved with the Civil Rights movement and practiced in the fine arts during the fifties and sixties. His directorial debut in 1969 gave him the chance to explore iconographic imagery on film for the first time. His use of the American flag as a symbol of corruption, bigotry, and violence is often understated but remains a constant throughout the entirety of the movie. Most notably, the flag is used on Peter Fonda's (Captain America) leather jacket, motorcycle helmet, and gas tank as an ironic reminder of American freedom. The films' protagonists stuff bank notes into the motorcycle's gas tank, a ploy used by Fonda and Hopper to react against American capitalism. The flag can also be seen in the background of shots filmed on July 4th and obvious acts of flag desecration are paraded as the movie camera travels through the southern states. Posters of the era helped the film reach iconic status, a film which for many symbolises the sixties counter-culture's quest for freedom and independence. When The Beatles first arrived in America in February 1964 they were quickly photographed in front of the American Flag and this striking image was used on the cover of Life Magazine, introducing Beatlemania to middle-America. The U.S. media has always understood the power of the Stars and Stripes and this picture is a clear attempt to portray The Beatles as American idols. A typical British view of the photograph would see The Fab Four as all-conquering hereos. In 1989, the artist Dread Scott exhibited his flag-on-the-floor installation at the controversial exhibition Old Glory: The American Flag in Contemporary Art, at the Phoenix Art Museum. Scott's What is the Proper Way to Fold a U.S. Flag? was publicly denounced by President Bush, Sr., and Congress passed legislation outlawing flag desecration as a result. Scott's installation simply consisted of an American flag placed on the gallery floor, a comment book placed above the flag (so that visitors would have to walk on the flag in order to sign the book), playing on the fact that the very first flag of the United States carried the slogan "Don't Tread On Me." Most of the people who attended the opening of the exhibition were Vietnam veterans. One protester said "That's my flag and I'm going to defend it, no son-of-a-bitch is going to do that... It just hurts because so many people died for this flag." Veterans removed flags from the exhibition (which included works by Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenberg, Ronnie Cutrone, and William Copley) and handed them in to museum curators. Ronnie Cutrone's painting, Hate, drew attention to itself because of its stark realism. The image graphically shows a member of the Ku Klux Klan holding a baby, as if the child is being sworn into the hate regime. Cutrone actually painted the image directly onto an American flag and hung the work on the exhibition wall. William Copley's Model for American Flag uses the simple image of the Stars and Stripes and replaces the field of stars with the word 'THINK'. An image often associated with the Vietnam War, the work asks the viewer to contemplate the many characteristics of America, its history and future, and its successes and failures. Model for American Flag represents a turning point in American political history and is an affirmation of the power of American modern art. The growing search for social conscience in the late sixties led to the founding of such movements as the Earth society in America during the early 1970s. A forerunner of the Green movement, it was heavy with philosophy, publications, and personalities, all of which influenced design directions and attitudes for years to come. One poster stands out from the many produced for the society. Ecology Now! uses the American flag as its main motif, the red, white, and blue transformed into monochromatic green. The poster represents an important turning point in American political history and reinforces the rise of the public's social conscience. The use of the Stars and Stripes is yet another example of designers using the country's most iconic symbol to subvert the notion of the American Dream. Robert Mapplethorpe's American Flag photograph from 1977 is one of the greatest examples of the resilience of the American Flag. There is something fragile and defeated about the image, and yet it is testimony to the endurance of the flag that, despite its appearance, stills flies in the wind. In the past fifty years or so, the Stars and Stripes have been abstracted, aestheticised and politicised in art and commerce, ad nauseam. The flag has become a classic, user-friendly icon, a long-standing symbol of heart-thumping patriotism accessible even to the most casual viewer. The Stars and Stripes are arguably the most graphic symbol in the Western world, as recognisable as the McDonald's Golden Arches or the Coca-Cola trademark. The "American Seal" is an image sold not only to citizens of the U.S.A. but to consumers worldwide. American branding has become associated with buzzwords such as democracy, opportunity and freedom. It could be said that America is no longer a country but a multitrillion dollar brand. "America is essentially no different from McDonald's, Marlboro, or General Motors"; the flag has what the French new-wave philosopher Jean Baudrillard called "commodity sign value," seen by many as the "registered trademark of America." The use of the flag in advertising is a violation of flag etiquette, and if proposed Amendments are passed in Congress then its use in advertising would be banned. Commercial advertising could well become the most pervasive offender of this new regime, meaning that companies such as Tommy Hillfiger, Nike, and Ralph Lauren would have to change their flag-based clothing and turn their existing inventories over to the US Government as illegal contraband. Companies such as Budweiser, Nike, and Pepsi-Cola continue to use the flag as a way of selling customers the "American Brand". Clothing companies such as Fuct and Tommy Hillfiger use the flag as a symbol of vitality and freedom. Their use of the Stars and Stripes as a ready-made corporate identity, which sells the spirit of America depicted in film and television, is very different from the actuality of American culture. In his book Culture Jam, Kalle Lasn argues that it is no longer possible to lead "a free, authentic life in America today." Lasn is the founding editor of Adbusters magazine, a publication that deconstructs advertising culture and has recently started a campaign called the Corporate American Flag. This flag, which swaps the stars of the Star-Spangled Banner for the corporate identities of major American companies, is being used in a countrywide campaign to encourage the American public to break free from corporate rule. Billboard posters have appeared in every major American city in an attempt to subvert the aims of corporate branding and to encourage free-thinking. Old Glory surely lost any symbolism of democracy and equal rights in the mid-sixties. Corporate American Flag presents a more honest symbol of modern American society. In 1999 Congress proposed a Constitutional Amendment that prohibited the physical desecration of the American national flag, a prohibition that, if passed, would be the first Constitutional Amendment of the freedoms set in the Bill of Rights. Congress have debated and rejected plans to carry out the Flag Amendment three times: in 1990, 1995, and 1997. The American public opposed the Amendment by a margin of 52% to 38% when they learned that it would be the first in history to cut back on the First Amendment, which protects freedom of expression. The Amendment would allow prosecution of protesters, artists, and other organisations who use the flag for political or artistic expression. The Amendment could criminalise the work of the artists discussed in this essay. The US Flag Code states that "the flag represents a living country and is itself considered a living thing". However, public flag-burnings have taken place in America since 1861, when Confederate sympathisers set fire to the Stars and Stripes during protest rallies in Richmond and Memphis, and Liberty, Mississippi. Acts of desecration continued into the 1960s and coincided with President Lyndon Johnson's decision to send US troops to Vietnam. Under a new legislation, any act of desecration would result in arrest. During times of national disaster and chaos, patriotism is rampant and the public turns to patriotic symbols. The tragic and horrific Terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington, DC on September 11th 2001 have led to an unprecedented outpouring of public grief. The American public has turned to the Star-Spangled Banner as a symbol of American unification and resolve. No other symbol shows America's resolve, or comforts or inspires like the red, white, and blue of Old Glory. Congress called on Americans to fly the flag for 30 days to provide a physical tribute to the memory of those who lost their lives in the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon. The American flag has dominated the country ever since the attacks and a media frenzy has turned the Stars and Stripes into the most iconic image in the world. Television screenings of crowds in Pakistan burning and stamping on the American flag have led to public outcry and an intensification of aggression towards many Asian countries. The American public are shocked that their country and its democracy is despised so much by the East. The American flag represents those ideologies. The growth of the media industry in recent years means that any event can be shown anywhere in the world at any time. The Terrorist attacks in America have ushered in an unprecedented media bombardment of images and information. The American flag can be seen on any news programme in any country. The American public and Government have turned to the national symbol in this time of crisis and it hasn't gone unnoticed by the news-hungry media. British illustrator Steve Bell commented on America's plight in The Guardian newspaper the day after the Terrorist attacks on America. His illustration shows the smoking World Trade Centre towers depicted as the Star-Spangled Banner to symbolise the damage to America's economy. Images of New York firemen faithfully recreating the iconic flag-raising image from Iwo Jima have been published around the globe, standing as an ironic gesture of remembrance and patriotism. Almost immediately after the Terrorist attack on the Pentagon headquarters in Washington, DC, a huge American flag was unveiled on one side of the building December 2001 saw the publication of Adbusters' "Epiphany Issue". The magazine focuses squarely on the aftermath of the Terrorist attacks and draws into question the American public's devotion to the national flag. The magazine cover, designed by Randall Cosco, uses an image of a burning Star-Spangled Banner, with a subheading that reads: "You're either with us or against us." Many of the magazine's readers are overly concerned at this new wave of patriotism. The letters page is full of pleas to the American public to stop displaying the flag. Justin Steffman wrote: "Put away the damn American flag and hang up a peace sign." So many people are shocked and scared at the outpouring of emotion that is entrusted in the Stars and Stripes; the trust it requires makes it an almost religious symbol. The American public has taken to wearing American flag pendants as an emblem of remembrance for those who lost their lives in the Terrorist attacks. Worn like a crucifix, the pendant is being worn as a token to ward off evil and as a guardian of American democracy. The artists discussed in this essay have all contributed to the debate that surrounds the American flag. It seems that their views have dissipated in the aftermath of September 11th. Is the American public really going to be open-minded enough to consider the work of Dread Scott or to contemplate the virtues of the Corporate American Flag campaign? The answer, in general, is no. The fact that Jasper Johns' first flag painting was used as the cover art of a compact disc, released as a tribute to the Americans who lost their lives on September 11th 2001, proves that many Americans have no understanding of irony whatsoever. Johns' painting is neither pro- nor anti-America. It is a painting that attempts to strip away any meaning and symbolism out of America's most recognisable symbol. The Terrorist attacks of September 11th have turned a flag that once stood for all that was good about American democracy into a symbol of remembrance or antagonism. The importance of the flag has reached its zenith. At no other point in history has the flag been revered so much by a pious American public. America is still recovering from the shock of discovering that other nations could hate what America, and its flag, stand for. The fact that Americans continue to unveil the Stars and Stripes during these times of hostility is almost inconceivable. The protection and display of any national flag is pointless and can only breed animosity. Artists like Gordon Parks, Faith Ringold, Robert Frank, and Dread Scott have all attempted to remove the Star-Spangled Banner from the American public's subconscious mind and place it into question. Faith Ringold's declaration that the American flag "should be burned and forgotten" is proof enough that it is impossible to use the Stars and Stripes as a graphic symbol without making social or political comment. It's curious to note the lack of importance graphic artists placed on the flag during Barack Obama's 2008 presidential campaign. Two of the most noteworthy campaign posters by Shepard Fairey and Scott Hansen overlooked the convention of the stars and stripes altogether, only adding the Obama '08 logo at the campaign's request. Instead we find iconic images that hint at a hopeful future, without the flag, using organic colours in place of the red, white and blue. These posters are an excellent example, if it were needed, of the role of graphic art to inspire people and promote change. The Obama '08 "sunrise" logo derives from the motifs of the stars and stripes with blue, from the flag, representing a new dawn and red stripes symbolising the great plains of America. Interestingly, the white stars from the flag are nowhere to be seen. President Obama's inauguration ceremony also stripped back the presence of the flag, which had previously been used as a rallying call, in what is a sensitive time for the country, particularly with regards to how America is viewed abroad. This revisionism marks a positive change in the American public's view towards their national symbol. The stigma attached to the flag is so strong that even its use on canvas (in the case of Jasper Johns) is a precarious act. This is, I think, the point. It's important that the American flag is seen out of context, subverted and brought into question. The flag is often used as a ready-made graphic symbol, a symbol that represents America and its values in the blink of an eye. Because of this, its use in advertising and television is widespread. Kalle Lasn states that "America has splashed its logo everywhere." The resilience of the Stars and Stripes cannot be underestimated. Its ambiguity makes it one of the most significant and influential symbols of the 20th Century. What other graphic symbol could possibly survive being interpreted variously as fine art, poster design, a fashion accessory, advertising, packaging, a social/political statement, or a national flag? |

|